Luis Hipólito Alén: Memories from his time as a professor, his connection with Duhalde, and his work in the fight for human rights

Jun 5, 2025

In a discussion with students from the Social Communication degree, celebrating the 40th anniversary of its founding, the professor reminisces about his most memorable anecdotes from the classrooms of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Buenos Aires. He also shares his experiences at the National Secretariat of Human Rights, his friendship with Duhalde, and provides his perspective on the ongoing fight for human rights.

Luis Hipólito Alén holds a law degree from the University of Salvador. Until his retirement, he was a professor and later the chair of the “Derecho a la Información” (best translation: Right to Information) course at the University of Buenos Aires. He also directed the Bachelor's Program in Justice and Human Rights at the National University of Lanús (Buenos Aires). Additionally, he served as the Undersecretary for the Protection of Human Rights for the nation from 2007 to 2015.

He has published several books, most of which he co-authored with his friend and business partner, Eduardo Luis Duhalde, whom he holds in high regard and fondly remembers. He even occasionally uses the plural form when discussing the political project they developed together. He made this point clear during a virtual interview he conducted from his home in Cariló (a beautiful beach resort town located in the Argentinian Atlantic coast) with students from the Social Communications degree. Sitting comfortably in his office, the professor began to respond:

- How do you remember your early years as a teacher? What kind of university did you find during those years?

- When the Social Communications degree program began, there was only one class dedicated to the subject of Derecho a la Información (Right to Information). The students expressed a desire for another class to gain more depth in the material, which led the Communication career director to invite us to contribute. At that time, Eduardo Luis Duhalde was the head of the new class. I have been a part of this class ever since, and I remember those years fondly. I found myself in a faculty that was still under construction; the program was in its early stages, as this second law chair was established only in the second year since the program's inception. This was also during the first years following the return of democracy in the country, which was in the process of building a new institutional framework. Despite being a new field of study, the Communications degree quickly became one of the most popular programs.

- During these forty years, what transformations have you seen in terms of teaching and the relationship with students?

- Teaching methods only changed dramatically when the pandemic hit. Prior to that, the approach was largely traditional. Over the years, we developed new techniques for several reasons. First, the number of students continued to grow, and second, we faced a building crisis. Imagine a classroom accommodating 70 or 80 students; it was incredibly challenging to maintain proper academic contact. I recall years in the mid-1990s when students had to sit on the floor because there wasn't enough space in the classroom.

“In a classroom where we sometimes had between seventy and eighty students, it was very challenging to maintain regular academic contact.”

But again, the most significant change occurred during the pandemic, which compelled us to reevaluate many of the paradigms that had shaped our lives. We transitioned from a traditional teaching model, where professors lectured in front of students and engaged in classroom discussions, to a distance learning approach. Although we have now returned to a state of "normalcy," we have incorporated virtual classrooms into our educational practices. This integration allows for more fluid communication with students.

- Can you share with us any anecdotes about the beginnings of the Communication degree?

- In the beginning, it was also a learning experience for us. One of the key issues we discussed while developing the program was a specific request from the program's first director, Enrique Vazquez. He emphasized the importance of highlighting our commitment to human rights.

I remember staying up late into the night, beginning with the basics of writing the program and recruiting the first group of professors. Eduardo was the tenured professor, Carlos Gonzalez Gartland served as the adjunct professor, and both Ricardo Esparis and I were the practical instructors for the department. At one point, Eduardo came up with the brilliant idea that the best way to fulfill Vazquez's request was to create a historical synthesis spanning from Mariano Moreno to Rodolfo Walsh. By highlighting these two significant figures from our history, we effectively demonstrated our commitment to freedom of expression, the right to information, and human rights.

I remember a student who often felt frustrated after class because he struggled to understand the material. One day, he approached me and said, "You know what? You annoyed me by talking so much about Moreno that I ended up buying a book about him. Now I'm fascinated by Moreno and I'm considering writing about him!"

All students should be familiar with the story of Mariano Moreno. He was a prominent figure for just over two years, from February 1809 to March 1811. In that brief period, without holding the highest office in the country, he made significant contributions that altered the course of history. Moreno was also the founder of the “Gazeta de Buenos Aires”, the first media outlet of the national era. It included a defining statement: "These are rare times of happiness in which one can think freely and express one's thoughts." This is a crucial message for students, especially those studying communication, as it underscores the importance of the right to communicate.

- How did you get into teaching? Was there a particular situation that motivated you to do so?

- The idea for the chair (or cathedra) originated from the students' request. At that time, my wife provided special motivation. I was already married to her, and she was studying Communications Sciences while also being an active political participant. She played a significant role in advocating for the establishment of a new Right to Information chair. One day, while I was with Eduardo Luis Duhalde, I received a call from my wife informing me that we had been proposed as professors for this new chair. The combination of her enthusiasm, Eduardo's support, and the students' desire for change all inspired me to embark on my teaching career.

- What improvements would you suggest, and what are your views on the current exercise of law?

- In fact, the law is a tool that the state uses to maintain order in society. Therefore, the law itself does not guarantee any specific outcomes. Its effectiveness is influenced by the forms of government that enforce it. It is important to distinguish between the concept of justice, which is an ideal we should strive for, and the judicial system. Unfortunately, many speakers tend to confuse the two when discussing these topics. The judiciary is one of the branches of government, and while its role is to administer justice, it does not embody "justice" itself.

“The extent of the right to information is democratic when those who enforce it are also democratic.”

One area that needs improvement is the judiciary. Currently, it operates in an elitist and corporatist manner, often limited by family connections. Furthermore, the judiciary is the only branch of government not subjected to public scrutiny; people do not vote for judges, nor do they know who they are, how they were appointed, or when. There should be some form of oversight regarding their performance. Therefore, a fundamental task of our times is to establish a completely reformed judiciary.

The right to information will be truly democratic only if those who implement it are committed to democratic principles. Many people claim that we have experienced 42 years of democracy, but I disagree. While we have had 42 years of elected governments and a level of institutional stability, democracy encompasses much more. It's not just about casting a vote occasionally; it goes deeper than that.

- How do you balance the relationship between academia, social reality, and politics? Given your active political life, how have you managed to create an impact from academia?

- The University of Buenos Aires serves as a platform for political discussion and debate. Students have the opportunity to elect their representatives, and we should take advantage of these spaces for dialogue within the faculties. I have had the privilege of being an active participant in political activities since I first entered the university many years ago. Additionally, as the son of a historian, I have been exposed to many individuals in politics.

I have also engaged in work closely related to human rights policies in this country. From my role in the now-dismantled Secretariat of Human Rights, I was able to contribute to fundamental tasks, particularly in developing public policies on human rights. One key area of focus was the right to information. For several years, I participated in the drafting process of the Audiovisual Communication Services Law (26.522). In fact, the faculty was one of the venues where debates about this legislation took place.

- Can you tell us about the process and the years in which you wrote the book Teoría Jurídico-Política de la Comunicación (The Legal-Political Theory of Communication)? Could you tell us about your relationship with Eduardo Luis Duhalde? How did he influence this process?

- Eduardo Luis Duhalde was a key figure in Argentine political history during the 1960s and 1970s. He was not only a historian but also worked as a lawyer representing political prisoners and unions. His significant contributions made him a prominent advocate for human rights.

“With Eduardo, we established a human rights policy that had been missing in nearly all governments.”

When I was a teenager, I read the history books written by Eduardo. In the 1970s, it was challenging for me to get close to him because, at the age of 20, Duhalde was exiled and went into hiding, making it difficult to meet him during that time. However, when he returned from exile, I happened to encounter Eduardo at a friend's wedding. I approached him and mentioned that we had a mutual friend, Alicia Eguren, the widow of John William Cooke. He responded, "So you're a friend of mine." From that moment until his death, we became friends. We saw each other daily and collaborated on legal, political, and social matters. We also co-managed a law firm together.

We arrived at the Communications faculty with a longstanding idea of writing a book. Building on our first book, “Sobre Derecho a la Información" 1993 (On the right to information) we sought a name for this new project. We wanted it to encompass more than just the right to information; we aimed for something broader. He, who was skilled at creating titles, suggested “Teoría Jurídico-Política de la Comunicación” (Legal-Political Theory of Communication). This title reflects our intention to explore both aspects and, importantly, how communication has shaped the relationship between the state and society throughout history.

Given our close connection—our families were friends, our children grew up together, and we even shared vacations—it felt as if we were living a shared life. However, everything changed when he was appointed Secretary of Human Rights in 2003. When that happened, he called me and asked, "When are you coming to work with me?" That's how we began our collaboration. We needed to establish a Human Rights Secretariat that existed only in name and develop a human rights policy, which had been missing in almost all previous governments. Our efforts had a significant impact on many laws.

For example, the Law of Filiations (14.367), the Law of Comprehensive Protection of the Rights of Children and Adolescents (26.061), the Law of Equal Marriage (26.618), the Law of Gender Identity (26.743), and of course, the Law of Audiovisual Communication Services (26.522) which was an old complaint that we had had.

- Chapter 4 of the book is titled "The Need to Create a New Information and Communication Order." Given this, is there still a necessity to establish a new order in today's context?

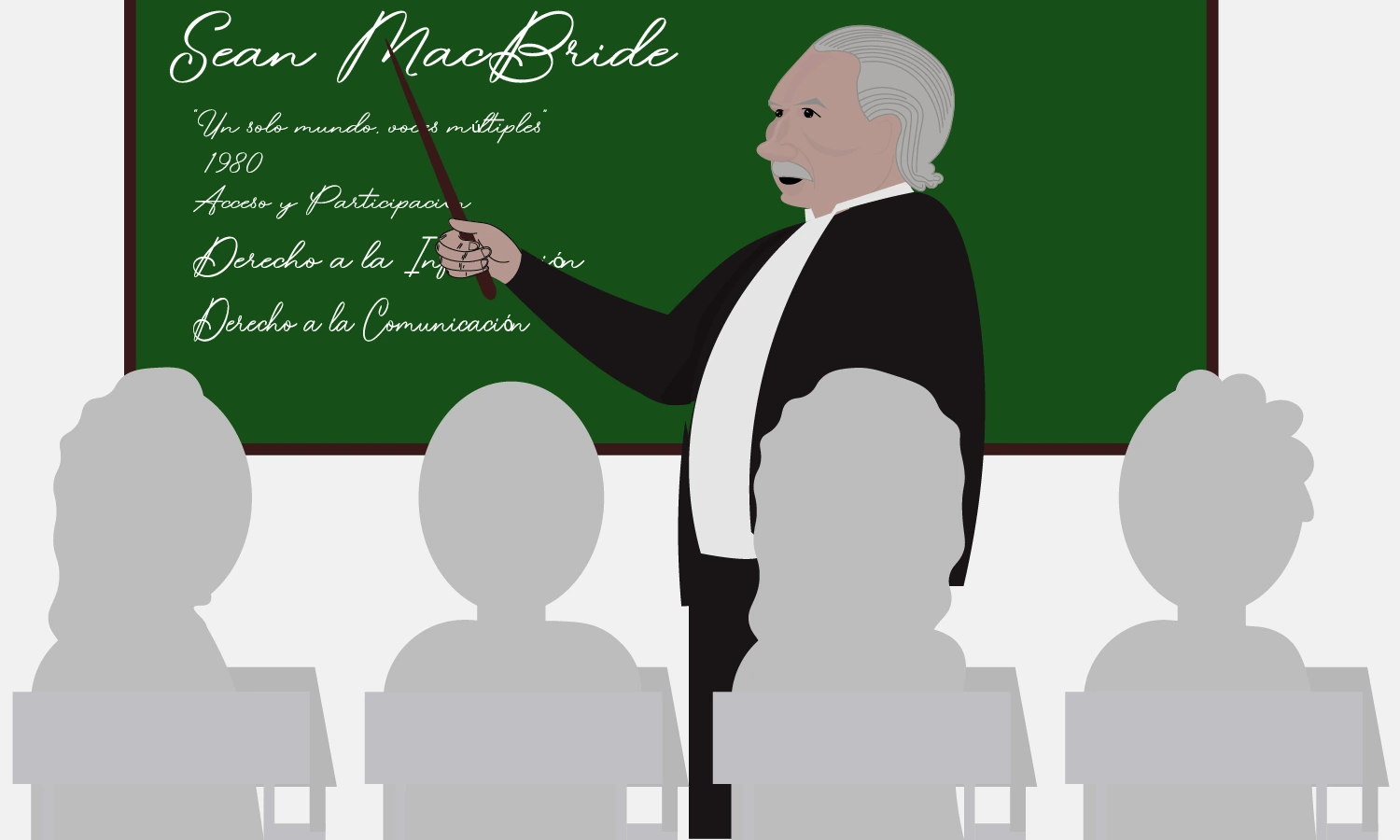

- Everything related to that chapter stems from a significant debate that led to the creation of the renowned "MacBride Report" during the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. This UNESCO group of experts, chaired by Sean MacBride—who was, interestingly, a friend and acquaintance of Eduardo—produced a report on the state of communications at the time. The report was published as a book titled "Many Voices, One World" (1980). I believe it remains essential reading for anyone interested in exploring changes within the communications framework.

If the communication and information landscape was unjust in the past, I believe it has deteriorated even further today. What was once warned about as a disastrous trend—the monopolistic concentration of media ownership—has now become a global reality.

I believe that the need for constructive change remains urgent, despite the challenges posed by technological advancements. We continue to confront many threats that were previously considered distant concerns, which are now unfortunate realities. While this is regrettable, it should also serve as a motivation for our commitment to building a truly democratic order.

- What was it like to discuss law during the country's emergence from dictatorship?

- I felt a sense of gratitude for the opportunity to develop something new and contribute to moving beyond a tragic era. Back then, we were free to create because the program did not impose strict limits on us; we could teach the material as openly as we wished, which was gratifying. It was fulfilling to know that we were helping to establish a democratic mode of communication. At that time, there was a strong emphasis on building, and the prospect of creating a different program, faculty, and university in another country was a real possibility.